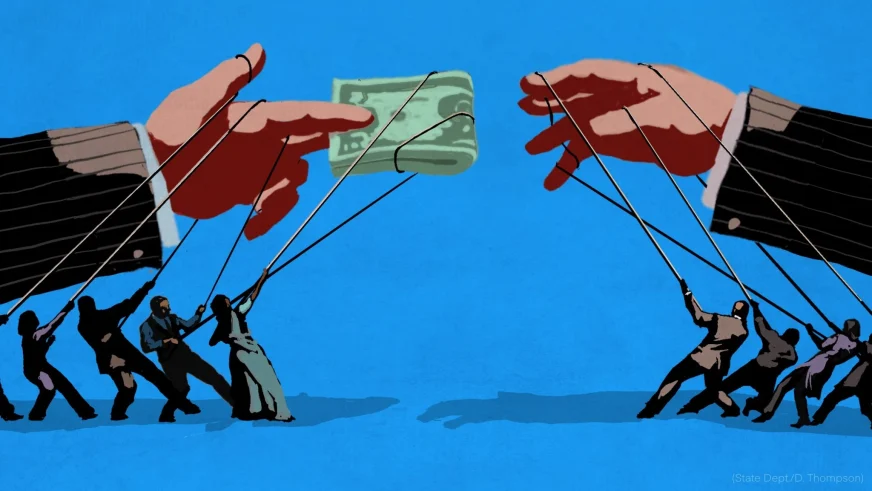

Is the Fight Against Corruption Losing Momentum in Croatia – and Across the Western Balkans?

22, September 2025

A recent commentary by Dr. Jelena Budak of the Institute of Economics Zagreb raises an urgent question: Is the global and national fight against corruption stalling?

Read the original article (in Croatian)

Croatia’s Backsliding

Budak points out that Croatia has slipped six places in the 2024 Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), ranking 63rd.

While the CPI reflects perceptions rather than proven cases, it remains a key barometer of trust in institutions. A fall of this scale signals growing public doubts about the effectiveness of anti-corruption reforms.

She stresses that laws and formal reforms alone are not enough. Real progress demands political will, independent institutions, and a shift in social norms. Yet several high-profile investigations—from Zagreb’s city administration to Varaždin county—underscore how deeply corruption still permeates local governance.

Warning Signs Beyond Croatia

The analysis resonates well beyond Croatian borders.

Both Serbia and North Macedonia continue to rank below the EU average on the CPI, facing familiar obstacles: politicised judiciaries, slow prosecution of cases, and limited transparency in public spending.

These regional parallels underscore that anti-corruption is not only a legal or technical issue, but also a long-term democratic challenge.

Troubling Global Signals

Budak also highlights worrying international trends.

She cites the recent suspension of enforcement of the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA)—a key global deterrent against corporate bribery—as a signal that even long-standing safeguards can be weakened for short-term gain.

Likewise, the OECD’s Exporting Corruption report warns that very few countries effectively prosecute companies for bribing abroad. Such global backsliding can embolden corrupt practices everywhere, including in South-East Europe.

What Must Be Done

The message is clear: corruption cannot be eradicated, but it can be contained—if the effort is persistent and credible.

For Croatia, Serbia, North Macedonia, and their neighbours, this means:

- Ensuring independent and well-resourced prosecution services (USKOK, special prosecutors, anti-corruption agencies).

- Expanding open data and transparency in public procurement and budgeting.

- Supporting civic education and watchdog organisations that build a culture of integrity.

- Strengthening regional cooperation, as corruption networks often cross borders.

A Regional Call to Action

Dr. Budak’s commentary is a timely reminder that anti-corruption is not a one-off reform but a continuous democratic commitment. Croatia’s recent CPI decline is not only a national warning—it echoes the unresolved challenges of Serbia, North Macedonia, and the wider Western Balkans.

Unless governments, institutions, and citizens renew that commitment, there is a real risk of backsliding—allowing corruption to regain ground quietly and undermine trust in public life.